Too many of us?

When I travel on the London underground and take an escalator up or down, I watch the faces of the people across going into the opposite direction. Usually, these faces are expressionless, on their way to something that will require some engagement but for now, on this metal vertical carpet ride, they’re in rest. I see people ahead of me getting off and I wonder about their lives, their goals and how that face is meaningful to someone somewhere. Then, forgive the morose thought, I sometimes wonder about the impact of a terrorist attack. In one blast, 100s of peoples’ lives would be ended or forever changed. I wonder how this would have an impact on those nearest to them and how community or government leaders (have to) respond. But there are so many of us. 7 billion in fact. What exactly is the impact of such a loss?

When the Charlie Hebdo illustrators were killed, discussions flared up about a value of a life. For some we hold vigils, for others we just read the headline and move on. Much of this is about proximity – we care about those similar to us, near us and less so about those further away. It’s an ingroup/outgroup phenomenon that is much studied in social psychology.

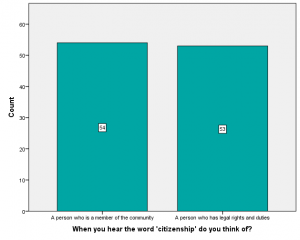

My work, in part, is to understand when and how people sense a belonging as part of their nation (Person Nation Fit). I’m currently analysing qualitative and quantitative data from people from a range of backgrounds and asked them questions about their own citizenship but also when they think someone else becomes a citizen and when the other should lose his/her citizenship. When international students were asked “When you hear the word ‘citizenship’ do you think of a person who is a member of a community or someone who has rights and duties’, the 107 who answered the question were split down the middle.

When asked to explain their answer, the replies varied but one respondent who opted for ‘member’ said “More than just being in the community residing and spectating, a citizen is an active member of the community” and one of the respondents who opted for ‘rights’ said “citizen is someone who have a right in voting and sharing the benefit with other citizen [sic] within the country”. Some felt it was a combination of both: “Actually I think about both. As a citizen, a person not only belongs to a community but also has the right and duties.” For now, I’m hypothesizing that the former (member of a community) definition is more tribal, linked to a sense of belonging whereas the latter (rights & duties) is transactional.

In our globalised world, migration is a hot topic, despite the fact that humans have been moving around for as long as we can track back records. Perhaps we are more bothered now, since the volumes of people have grown. Yet, I doubt many of the people who ride the escalator up or down think about their citizenship much, unless they’re in the process of pledging their allegiance, if they’re a refugee/asylum seeker or if they’re about to migrate elsewhere. I’m unsure the majority can remain ‘laissez faire’ about migration, in that, if we’re not opposed to it, we cannot choose to remain neutral. If I invite you to my home, I show you where the kitchen and bathroom is. I don’t let you get on with it and figure it out so you make mistakes and then I get annoyed, especially if you brought your husband and parents too. One needs to invite the other to the proverbial fire, sit with them, share with them. The rules of pragmatic multiculturalism have changed and that requires engaged and culturally intelligent management.